It had to be thirty years since I’d last spoken to Mark. He contacted me out of the blue on Facebook’s messenger. I didn’t even know the App existed until his name appeared on the screen in front of me. I’d often wondered where he was, how he was getting on, but I never got around to tracking him down. My people (geographically-generationally speaking) never fully embraced the mysteries of social networking and so any attempt at tracking them down invariably hit a brick wall.

We were work colleagues before we became friends. Full of energy and fun-loving he was eager to party with an Irishman on a working holiday newly arrived in Sydney. After all those years I didn’t recognize his face when he appeared on the monitor but I remembered his voice straightaway. Mainly because of the way he greeted me, the same way he always did: “Heh, Irish.”

Now to many of my fellow country men and women this would send a shiver through their homicidal spines right down to their vestigial green tails and I have to say initially I was a little taken aback. I was suspicious as to his motives but as I got to know him better I understood Mark didn’t intend it in a mean, disparaging sort of way. You knew he was excited to see you. You felt valued not in spite of your Irish-ness but because of it. To Mark, the term Irish was not a sneering jibe at my intelligence or sobriety, it was a term of endearment, of bawdy solidarity almost, of brotherhood.

Now I’d been christened Irish before and by people very different from Mark. So much so that I grew to loathe the term. It was a label like Paddy or Mick. It meant a number of things to my ear mainly, stupid. Of course depending on which part of the english speaking world you hailed from coloured your personal understanding of its meaning. To some it can translate as drunkard or papist. To others terrorist, treacherous even with no basic understanding of loyalty. A spineless coward and mindless brawler all at the same time. A gambler and thief. A sex-starved grub with only one thing on his mind or a backward simpleton bewitched by the spell of the local parish priest.

There are many derogatory slurs for different nationalities, but very few like Irish that use the victim’s nationality or ethnicity as the point of humiliation. Why was it, I asked myself, with so many slang words available to the casual racist they choose to deride me with the country of my birth? Irish simply means an ethnic group native to the island of Ireland. Was Ireland the only country where the collective name of the native people was regarded as a racial smear? Apparently not.

There is of course Aussie and Brit but these are merely a shortened form of the collective noun and not in the majority of cases derogatory. What I’m thinking more of is; (1) Chinaman – described as being offensive in most modern dictionaries. The Chinese Exclusion Act 1882, prohibiting the immigration of Chinese labourers into the United States referred to Chinese people as Chinamen; (2) Polack – a derogatory references to a person of Polish descent. In Poland, Polak denotes a Polish male however more recently in the English speaking world it has come to infer stupid or primitive. This negative stereotype which had its genesis in the propaganda war machine of Nazi Germany spread throughout America finding its zenith in the 1970s; (3) Paki – as derived from Pakistan. Viewed as pacifists or ‘passive objects’ Pakistani’s were seen as easy targets for the Paki-bashers and skinheads of 70s London. A concurrent campaign against racism reported more than 20,000 racist attacks on British people of colour, including Pakistanis, which sparked a series of riots throughout Britain in 1985; (4) Lebo – described as a person from Lebanon but now seen as an ethnic slur especially in Australian denoting mafia gangs and drug lords; (5) Russkie – a native of Russia. Not so much a derogatory terms as a challenge having its origins in the Cold War. More recently it has come to be associated with organised crime.

The animosity for the Irish however goes back a long way in British imperial history. Centuries. Only with the spread of British colonialism was the rest of the world introduced to this historical contempt. The discrimination was initially rooted in anti-Catholicism and the Irish refusal to convert to Protestantism, yet strangely the origins of anti-Irish sentiments have a more sinister beginning. The Catholic Church itself paved the way for the long-standing animosity by which the Irish were soon regarded by their Anglo-Norman masters.

In order to secure the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Ireland under the Archbishopric of Canterbury, Pope Adrian IV (the only Englishman to serve in that office) issued a papal bull called Laudabiliter that gave Henry II of England permission to subdue Ireland as a means of strengthening Rome’s control over the Irish Church. In the following 800 years the English conquerors were notable for their extraordinary feats of cruelty and barbarism typical of most European colonial states. However there was one event more than any other that highlighted the terrible link binding colonialism and discrimination.

Between 1841-5 it is estimated that The Great Hunger (generally referred to as the Potato Famine outside Ireland) resulted in the loss of over 3 million people in Ireland.

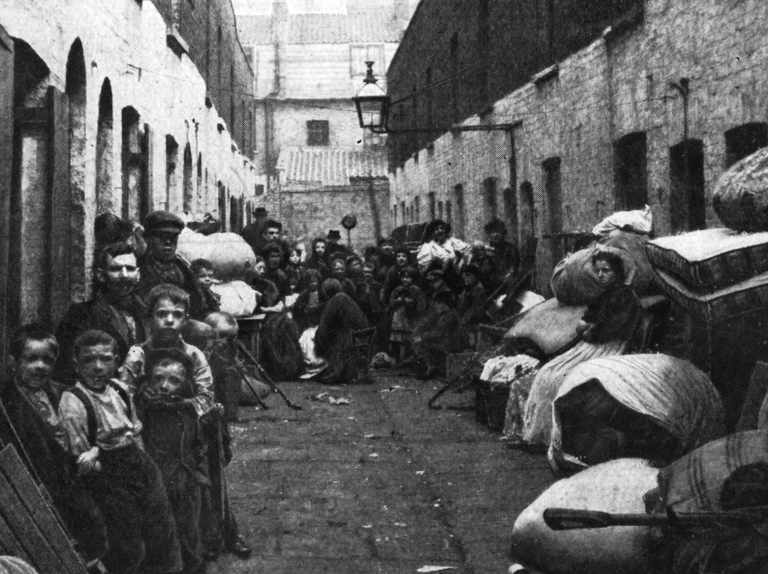

About 1 million people died and perhaps 2 million more eventually emigrated. The events of that dark decade spurred a further century long decline in population. Like today with the spill of millions of refugees across European borders it didn’t take long for tensions to arise. Anti-Irish sentiment as it’s euphemistically referred to saw an almost immediate sacrifice of empathy to be replaced with prejudice and antagonism, the basic nuts and bolts of discrimination.

Popular during that period amongst the Whigs and Tories in the House of Commons were the population theories of the Reverend Thomas Malthus. In 1817 Malthus stated: ‘The land in Ireland is infinitely more peopled than anywhere else; and to give full effect to the natural resources of the country, a great part of the population should be swept from the soil’. And while today the Irish Government may .. cherish its special affinity with people of Irish ancestry living abroad who share its cultural identity and heritage (Article 2 of the Constitution of Ireland) .. the legal definition of citizen recognises only some 3 million people, of whom 1.47 million are Irish-born emigrants, the balance made up by their children enrolled onto the Foreign Births Register. Even today with a population of 4.784 million living in Ireland, thirty-eight percent of legally recognized Irish citizens live outside Ireland.

The struggles of those first emigrants to foreign shores wasn’t that dissimilar from those left behind. Friedrich Engels, writing on the Irish escaping to Manchester commented: ‘The race that lives in these ruinous cottages, behind broken windows, mended with oilskin, sprung doors and rotten doorposts, or in dark wet cellars, in measureless filth and stench … must really have reached the lowest stages of humanity’.

Almost a century later in 1934, J. B. Priestley wrote in his travelogue, English Journey, an appeal for democratic social change, ‘If we do have an Irish Republic as our neighbour, and it is found possible to return her exiled citizens, what a grand clearance there will be in all the western ports, from the Clyde to Cardiff, what a fine exit of ignorance and dirt and drunkenness and disease.’

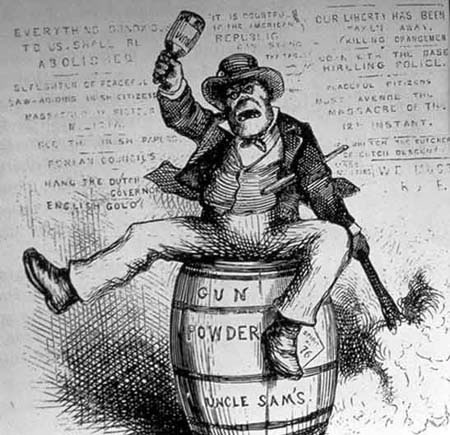

And of course it wasn’t just Britain in which the Irish refugee was forced to endure discrimination. It is estimated that as many as 4.5 million Irish arrived in America between 1820 and 1930. In the 1840s, they comprised nearly half of all immigrants. During the years of the famine a flotilla of 5000 boats jettisoned 85,000 passengers out onto the docks of the eastern ports. They settled within walking distance of the docks in rancid tenement slums. Diseases we associate with today’s refugee camps like diarrhoeal diseases, hepatitis, typhoid and tuberculosis were common. Of all the immigrants flooding the east coast the Irish were the most vilified because of their catholic faith. Their loyalty to the Pope was seen as a threat. Mobs burnt churches and hunted down victims, notably in Louisville, Kentucky in 1855 when an armed gang attacked Irish and German Catholics killing up to 100 on a day remembered as ‘Bloody Monday’. The Irish took the lowest paid jobs building roads or working down the mines, those jobs for which they were permitted to apply. Riots broke out for the control of job sites. Pitched battles erupted between Irish and local American work teams competing for construction jobs. Secret protestant societies sprang up in response to the papist invasion. This anti-Catholic reaction reached a peak in the mid-1850s when a movement called the Know-Nothing Movement tried to oust all Catholics from public office.

Often the Irish character was measured by perceived physical characteristics. They were the subject of vicious caricatures which portrayed them as apelike which went a long way in the native mind to explaining their violence and savagery.

Sadly immigrants and refugees haven’t fared that much better. We don’t appear to have learned from the experience of our ancestors. Being a victim of international discrimination has not made us a more empathetic and compassionate people. We, like every other ethnic minority, are swayed by the colour of a person’s skin, their creed and culture.

An ENAR Ireland (European Network Against Racism Ireland) quarterly report for June 2014 states, ‘people from across almost the full range of minorities in Ireland are consistently reporting unacceptably high rates of racism’. It further states:

… an increase in reports of incidents targeting Jewish people reminds us that antisemitism is sadly as real in Ireland as it is in other parts of the world. This dubious honour also holds for incidents perpetrated against Roma and against Muslims, just as it does against Asians and migrants from central and Eastern Europe. No racialized group is exempt from the widespread racism that people experience in Ireland. This is the reality which Irish Society and its institutions must face.

A report issue by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights in November 2018 ranks Ireland as the second worst EU country after Finland for racist violence against black people. Out of a sample group of 5,800 people, 51 % of people of African descent living in Ireland said they had experienced hate-motivated harassment, compared with 21 % in the UK.

In the UK, Irish Travellers (growing up in Ireland we called these people gypsies and tinkers) have been recognised as a distinct ethnic minority for 13 years however in Ireland Travellers’ have health profiles similar to third world countries. Their mortality rate is three times the national average while their suicide rate is six times.

In America the Irish immigrant discovered a new hierarchy based not on faith but the colour of a man’s skin and by proving that they could be just as brutal if not more in their oppression of African Americans they were able to gain ready acceptance by their new masters.

As a young traveller in 1975, I had my own encounter with the meaning of being Irish on an alien shore. Coming up from the London Underground onto Leicester Square I found the newsstands and neon billboards emblazoned with the headlines – IRISH BASTARDS. An IRA bomb had just gone off in the London Hilton leaving 2 dead and 63 wounded. The city went into melt down as Special Branch hunted for the bombers. I spent the rest of the day hiding my accent until I was safely back in the Crown bar in Cricklewood. It was a bright sunny day but the curtains were drawn. The mood was sombre as we waited for whatever was coming through the front door.

On the boat back to Ireland 24 hours later I could feel the steely eyes of customs security glaring first at my student identity card and then at me. No passports were required to travel back and forth across the Irish Sea so my student card had to do. This was my first experience of being something other than native to the land in which you were standing. I was a foreigner. Worse still, I was a foreign threat: I was Irish.

When I arrived in Australia I encountered what I could only describe as a cool Irish sentiment. For the first time in my life I was referred to as Irish. It wasn’t common but I endured the phony Irish accent and some days it felt like I was the top of seemingly everyone’s morning. Back them my accent was stronger, my confidence mostly unshakeable. I still had a lot to learn about the world.

I encountered the term un-Australian; anything that didn’t fit in with the worldview of the person using the term i.e. it was un-Australian to drive anything other than a Holden ute; eat sushi or pasta; drink wine or foreign beer; play soccer, etc. It is said that Australians deny the existence of racism. That their very generous immigration policy is based on need. That multiculturalism is simply a euphemism for the absorption of other minorities into a greedy economic engine. But there was something else here. Something other than simple racism. I soon got to know these Aussies. They became colleagues, friends and family. I realised there was a distinct shift between our cultures. We were different in many ways especially in the way we expressed and managed our relationships with other people. My treatment had as much to do with how Aussies express themselves as my national identity. In Australia one can be quietly proud but not intractably so. There’s no room for false pride either, especially to a foreign sovereignty, one that you left behind for a better life.

Australian pride however is considered a different thing altogether. There are some who insist it is beyond reproach. And though often equated with the sacrifice of humble diggers in the two world wars there is now swell of other voices and opinion regarding the meaning of being Australian. One important voice speaks louder than all others.

Although the Aboriginal people arrived in Australia well over 40,000 years ago it wasn’t until the 1967 referendum that they were first included in the Australian population census. And although over 80% of Australians believe multiculturalism is good for the country the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders would indicate otherwise.

National pride and racism are staple components of the human condition here in Australia as anywhere else in the world. In 2018 one in five people living in Australia experienced racist abuse.

I’d like to think that having experienced racial abuse one would no longer be capable of inflicting it but that is simply not the case. Racism is a ready tool in our defensive mechanism. It’s part of our genetic makeup. We are continually aware of our differences and as such we are conditioned to treat others differently. There is no nation without fault just as there is no people without a history. On writing about racism the American poet Claudia Rankine said, “You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you.”

But the world is changing. It is quickly moving beyond our understanding. Multiculturalism is no longer a post war philanthropic exercise in the pursuit of justice, wealth and empowerment for all – it is now a matter of survival. Take Japan for example. Japan is the oldest large country in the world. More than half of its population are over the age of 46. More deaths and fewer births means Japan’s population is shrinking. The Japanese Statistics Bureau estimates that the population will fall to just over 100 million by 2050, from around 127 million today. Assuming no change in migration or fertility rates, the population will fall to 8.5 million by 2300 and 2 million by 2800. The only realistic solution is immigration however Japan rejected more than 99 per cent of the 10,901 refugee applicants for asylum in 2016. It accepted only 28 people. That was an increase of one person on 2015’s intake.

I believe the two biggest obstacles to racial equality are pride and nationalism. It is widely accepted that pride is driven by poor self-worth and shame. We feel bad about ourselves so we compensate by fabricating feelings of superiority. We look for flaws in others as a way to conceal our own. We relish their shortcomings while all the time turning a blind eye to our own failings. The Chinese Communist Party defines patriotism as loving your country however nationalism is defined as blind love for a country through denial of its imperfections.

So here’s the thing. The term Aussie, commonly used in Australian to denote a version of self, is considered a rallying cry and a sporting challenge. On a personal level it can be a mirror onto personal values. There is another word. One could say it appears at the other end of the spectrum to Aussie if such a spectrum did exist. It is one the one word in the racist lexicon that I once ranked alongside the word Irish. That word is Nigger. Anyone reading this will undoubtedly have some appreciation of the universal impact of that word. As a child I felt it a vile injustice although I had no real understanding why. The mere presence of the word felt like a threat. It was an unnatural word, a word that deserved to be erased from human memory like Pox or Bubonic or Nazi. But amazingly over time the complete opposite has occurred.

Now Nigger has very little to do with skin colour. See for example Kanye West’s use of the word in ‘Gold Digger’. Or Boaz Yakin’s movie ‘Fresh’. Its intrinsic meaning has completely changed. Although the African American Registry laments the unremitting endurance of the word and the ultimate effect it has on black society, the word is now interpreted in terms of survival; culture, history, and experience. It is the underlying connection. It equates to strength and African America solidarity. It means community support, resilience of spirit and defiance. It is a byword in the history of urban American soul. The word Nigger is no longer available to the KKK or any small-minded, right-wing, flag-waving cohort of bigoted racists because that word now belongs, body and soul, to black American.

So where does that leave Mark and his use of the word Irish? term of affection or disgust depending on your persuasion. But as I said previously – there is something different happening here. Prior to the civil war in American it was not uncommon to malign Irish immigrants as White Negroes (or Afro Americans as smoked Irish) yet amazingly in Tasmania I have come across a number of headstones that affectionately include the deceased’s nickname in the inscription – Nigga, on account of the person’s suntan.

Mark never understand the effect of calling me Irish. He never understand the evil spell that word had over me when wielded with malicious intent. Irish is somehow worse than Paddy. Paddy is individual; I alone am stupid, ignorant, addled. Whereas Irish is everything about you. It’s not just you, it’s genetic. The problem is your family, your town, your country, your race. It’s absolute and irreversible. Something beyond your understanding that only those sneering faces gathered around you can truly comprehend. You’re just too dumb to see it. Too Irish.

Mark never used it that way. And because of that I was able to understand something very important. Irish is just a word. The power it had over me was the power I had invested in it. It was my Achilles heel, constantly exposed. I was openly Irish and had little or no defence. It was at once my ethnicity and my shame. And then one day I realised that there was no shame. There were shamers, yes but it was I who chose to feel ashamed and all because of one little word. A word, on one hand loaded with guilt, suffering and innuendo. And on the other hand rich with culture, history, music and people. The Irish.

It’s a great thing to be Irish; English, American or Australian. It’s a greater thing still to be human, whatever your ethnicity – colour, race or creed. We are after all recognised primarily as coming from the same human species before the other tribal boundaries come into play. Whatever nation we identify with, whatever race we were born into; we are human first and last.